Author: ROMPoetry

Valuing Simple Creative Time

Valuing Simple Creative Time: The Night Under My Wing

Last week, I had the privilege of spending two days with some 6th grade students, when I was hired through the Arts Council to do a creative writing program with them. In only two days, you can only do so much of a program. And also, in two days, you can do and see and feel so much.

It has been nine years since I was a full-time teacher in a K-12 classroom, and those nine years did not feel as if they had passed at all. There are still awesome teachers doing the work with few resources, too little time, too many arbitrary rules and too many students.

AND, there are still students who are our beloved human beings who want to be heard and seen or desperately want to not be seen or heard, who want to do the right thing, who have no frame of reference for the right thing, who are diverse and annoying and joyful and worthy of so much more than we can ever do for them.

We wrote poems about their hobbies and mixed those with words about flowers and we drew pictures and illustrated a N. Scott Momaday poem and wrote their own “Delight Song” poems. I have very few rules in these activities so no one broke them, and they created things that followed no rules I could have given anyway.

One boy took a brief line from Momaday’s poem and added another line and then created an entire-novel-length story in his head about what his illustration of it all meant. He was very serious, and so was I as I listened to him tell his story.

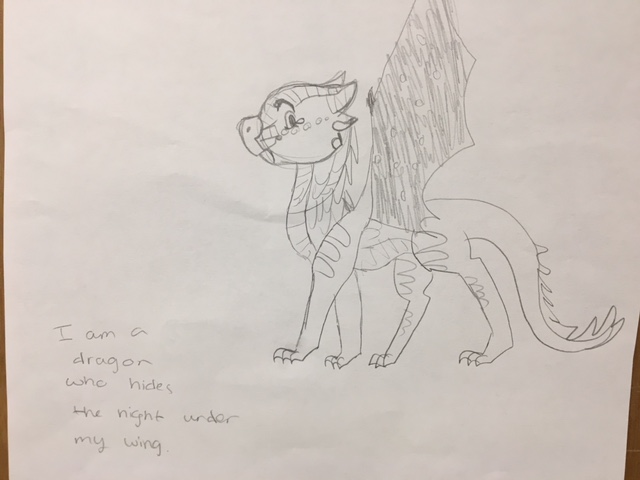

One girl wrote no words but drew a lovely dragon-type creature for me. I wrote on it, “This is lovely, and I would really like to see some of your words to go with it.” The next day, she added these words to it, “I am a dragon who hides the night under my wing.”

“That is awesome,” I told her and tried to hand the paper back to her. And she said, “No, it’s for you.”

It is now hanging next to my desk in the museum office. I could go on with other examples, but they all go to explain how important reading, writing, listening, sharing, and creating art and poetry are to us.

We must make time for these things. We must value them every day. Finally, I refuse to believe we can’t find more and better ways to do these things.

How to Write a Poem

by Shaun Perkins

There is a wonderful French police drama called Capitaine Marleau, in which the title character solves crimes in a unique way, without “thinking” or “believing.” Her response to her colleagues who ask her, “What do you think?” is “I don’t think. I observe.” And her response to the question, “What do you believe?” is “I don’t believe. I’m not even baptized.”

Why I love this character so much is because she is poetry in action. There are two rules to writing poetry: 1. Observe something. 2. Write about it.

This is Marleau’s modus operandi. She comes to the scene of the crime, observes the situation, and then “writes” about it by putting the details of that observation together, without emotion, in a way that makes sense for understanding the crime.

Poetry is not about emotion. When Wordsworth said that a poem was “emotion recollected in tranquility,” he meant that the poetry came from remembering and writing about the experience that caused the emotion.

A poem is designed to evoke emotion in the reader and listener. The way to evoke emotion, to pull strongly at someone’s soul in the most powerful way, is to deliver the detail of an experience that shows you truly observed and witnessed it.

This is also the way you solve a crime such as murder. Objectively investigate the facts of the case and put them together without artifice to reveal the truth—the killer’s identity.

“Without artifice” is a key here, as a clever DA or lawyer can always twist the facts to make them fit a certain scenario. A poet will not twist facts or inaccurately use language in order to deceive, unless we are talking about satire and the like.

So, this is not a traditional explanation of how to write poetry, but it is the easiest way to explain something that is actually quite difficult. Many people are not that observant or understand that poetry demands this quality. Tons of bad poetry exists because too many people think that a poem is about how they think or feel about what they observed, not the actual observation.

It is much easier to describe how we think or feel than it is to describe a thing with effective nouns and verbs. That’s another way of defining what a poem is: A description of something with effective nouns and verbs. I mean, it’s not a lovely description, but it is apt.

Some might fear that using this advice would lead to a boring poem. The opposite is true. Be honest: Aren’t other people’s thoughts and feelings boring most of the time? What is interesting is the stories they tell, the observations, the details they have observed and share in conversation.

And also, be honest: Do you want someone giving you unsolicited advice, or even worse, feeding you propaganda? That is what happens when you forego the detail and go straight to the message. This is why Capitaine Marleau said she did not think or believe because in those things, mistakes are made if they take precedence over the event, the result of the processes of actual physical life.

Of course, a poem can have a message or theme and should definitely have some sort of emotional effect on the reader, but that theme and effect both derive from the poem’s effectiveness in creating a picture through sensory detail.

So here is how you write a poem: 1. Observe something. 2. Describe what you observed.

Try it and see what happens.

Eros in September

The dotted dirt floor around Psyche’s feet pulled me into a story of another’s trials. I held the image of my love for a few seconds, and then I turned away, turned back to the stories of childhood. Even my non-human childhood held stories, for we always wanted to understand how human minds worked.

The dotted dirt floor around Psyche’s feet pulled me into a story of another’s trials. I held the image of my love for a few seconds, and then I turned away, turned back to the stories of childhood. Even my non-human childhood held stories, for we always wanted to understand how human minds worked.

Once upon a time, a girl

came out of the closet of her room,

the broom already in hand,

the dustpan hanging like a charm, clanging

against the metal band around the smaller

straw hand broom hooked to the rough rope

serving as her belt. What does one need

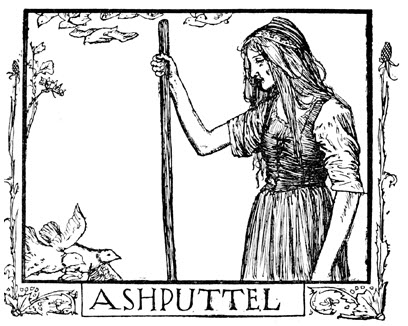

to understand this picture? There were seeds spilled across the otherwise perfectly swept brick floor. As a child, I stopped my mother in the course of her reading it to me, right here, right at the picture, a double-spread bleeding across two pages, book stitches in the brickwork of the chimney. The girl with the hem of her skirt in tatters, the girl pondering the work.

I edged away from stories and books. I flew above living pictures and through open windows and never saw a girl quite like that one in the book of fairy tales. I began to imagine that no such person existed, that the story was false, that all stories are false. The book’s cover split with the changing of the seasons, and silverfish swam in the falseness of the yellowing pages.

And now I am drowning in story. I dove deep into her rescue and became the hero between the pages. Our life revealed the conflict essential to the continuance of the myth. Her journey is the pattern of a life throughout time. I must have known this when I was five or six. When I pondered that three-color picture, I didn’t know to ask: What does one need

To sort the seeds? What tools?

To sort the seeds? What tools?

She had two brooms and a dustpan.

She had the willingness to work hard,

Good eyesight, the strong knees

And lungs of youth—and perhaps

Most important of all—the experience

Of loss rupturing innocence.

What did I know of loss until Psyche? There is a cynicism that some of us wear to hide the knowledge that we are intact. We haven’t experienced loss. We wear the badge of our completeness, obsessively self-aware like Doric columns defining the entrance to a building lacking ornamentation.

The seeds in the picture might as well have been ants or pebbles or splatters of paint. I could not distinguish what they meant as seeds, nor as anything else. Yet, when I sat on the window ledge yesterday and looked past the fading light of the day to the image of Psyche at my mother’s side, I could tell they were seeds. I even knew where they came from.

The seeds in the picture might as well have been ants or pebbles or splatters of paint. I could not distinguish what they meant as seeds, nor as anything else. Yet, when I sat on the window ledge yesterday and looked past the fading light of the day to the image of Psyche at my mother’s side, I could tell they were seeds. I even knew where they came from.

Last night, I flew from the window and walked into the forest. I found the cow parsley, growing taller than I, its weedy white heads framing a pond long since abandoned by man and animal. I rubbed one of the dead flowers in my hand and the seeds trickled across my palm.

I put the seeds into a small leather bag and continued around the pond. Over the ridge was a heath, only marked by small deer trails zigzagging along the edges and trailing from pond to the cover of deeper forest. The combined sounds of night and the singers of the night rose around me so that I could no longer hear the tips of my wings raking against the heather. When I crossed the heath, the seeds clung to my feathers. I brushed some into the bag and left the rest to fall on their own.

Near the road leading into the town of Psyche’s abandonment, a hazel tree grew in its crooked way, dusty and beckoning near a ditch. That long ago storybook girl knelt at a tree like this, a tree like this her mother was buried under. Doves dipped their wings beside the blossoms and held on tight to the tiny branches. Fallen flower petals dotted the grass beneath the tree, a picture not unlike that of the seeds on the hearth. There is a way of looking at things, of listening to the souls of those who set them in motion that alters our perspective.

Perhaps our lives are abandoned

To the tools that echo our presence

Into being. What did she have at birth?

A voice. A hunger. An ability to fill

And evacuate. A sense of the tunneling

Of another’s life through her own.

Was it the contrast of life before and after her mother that held me to that story? The story that held onto me. And so many others that may be holding you . . . motherless children–the girl with ebony hair and white skin, the girl spinning straw in the prince’s basement, the boy escaping in his raft to the Mississippi River, the boy with the lightning scar on his forehead, the child in the cinders and the boy from Tintagel and the girl wandering to Carter Hall, the girl traded for the theft of a rose.

Where am I in these stories, and where is Psyche? Where are you? How will I know which story to continue to hold onto? I sort the versions and note their similarities. I have come to the road that leads me to those who gave her to me, though they didn’t know they were doing so. What do we give ourselves to when we have been abandoned, when we abandon the first draft of our lives?

Where am I in these stories, and where is Psyche? Where are you? How will I know which story to continue to hold onto? I sort the versions and note their similarities. I have come to the road that leads me to those who gave her to me, though they didn’t know they were doing so. What do we give ourselves to when we have been abandoned, when we abandon the first draft of our lives?

Would I even think these stories odd if I also had no mother?

Taking care not to trample the hazel blossoms, I left the road and continued across the grass. My wings ached to fly. My body remembered the earthly attraction of tender clover under my feet, the perfume of a grasshopper’s wings at knee level, the sudden rustle of rabbits and lizards at my approach.

I jumped over a small tree felled by the last storm, and the leather bag fell to the ground, the seeds spilled out in a pile. A breeze swept them up and swirled them into a miniature tornado that lingered beside me and waited somehow for me to interpret it.

I jumped over a small tree felled by the last storm, and the leather bag fell to the ground, the seeds spilled out in a pile. A breeze swept them up and swirled them into a miniature tornado that lingered beside me and waited somehow for me to interpret it.

Once upon a time, a girl was born or you were. You flooded the world with the question of yourself, your toes even curled into the mark of your coming, the entrance the end of a sentence your parents began.

Your fingers met your toes and said hello. The girl played in the creek behind the house and caught minnows in her cupped hands and let them go. You played with moon, who spoke to you with its shadows and light when you lay in the grass of your front lawn or the bedroom of your childhood.

I spoke what I felt and didn’t know what that meant. The girl laughed at her mother’s jokes. You smiled when you caught the red ball. She cried when no one understood, not even those closest to her. I wanted to break free. You stayed out after curfew because you couldn’t stop kissing the lips of the one who was reshaping your world.

You left home. You came back. You left home. Others left you. The girl spoke her last words to the woman of the doves, the last words the woman would hear. I wanted something that I couldn’t imagine. The girl lost her father who still slept ten feet down the hall. You did the work that found you.

I have never done the work that is mine. I am just beginning. The girl had to hack dreams out of rodents and barn wood to escape. She will never escape what her body remembers. You will never escape what your past became, even from that moment when your thumb was saying hello to your toes.

Separate the stories from the life and . . . I dare you . . . separate the stories from the life. I had a love affair with the end of days, and that was where I went wrong. You are reclaiming that root wrapped around the seed, around the rock, around the bit of glass, around the skeleton of the mole because you are seeing the parts, and you are seeing . . . the parts.

The girl wore only one pair of shoes for the rest of her life—orange house slippers, worn, warm, molded to her feet as sure as magic.

–Shaun Perkins

Don’t Fear the Poem . . . or the Museum

I’m working at the ROMP Rummage Store today, and as always, I’m trying to get customers to go to the museum–it’s only 2 miles outside of town. It’s easy to find. The door is open, the lights are on, air conditioner going. A lot of people have no interest in poetry. One woman today said, “I’m scared.”

I’m working at the ROMP Rummage Store today, and as always, I’m trying to get customers to go to the museum–it’s only 2 miles outside of town. It’s easy to find. The door is open, the lights are on, air conditioner going. A lot of people have no interest in poetry. One woman today said, “I’m scared.”

I said, “There’s no one there. The door’s open–just go in and look around at your own pace.”

I didn’t convince her.

But seriously, don’t fear the poem. Don’t fear the poetry museum.

This museum is for and of the people. You can touch stuff in there. Write on walls. Listen to a jukebox. Sit in an easy chair and read some old autograph books from 1930. ALL of the poetry in it is written by regular people like you. Don’t fear it . . . please.

It’s only called a “museum” because I wanted the acronym ROMP when I started this place 4 years ago.

If you came out to the first museum, this one is quite a bit different. It’s in a different building, across the pasture from the old one. The exhibits and your interaction are different. Come see.

There’s no one there who’s going to tell you how to read the poems or write a poem or what to look at or think or feel. It’s a trusting place. Go in and see.

Don’t fear the poem.

–Shaun Perkins

The Beacon of May

In May, the leaves of the redbud beckon

In May, the leaves of the redbud beckon

me from the window where I look

Out

Instead of being

Out

“Beckon” comes from an Old English word

Meaning “beacon.”

May is a beacon with its multiple layers

Of green and delicate white,

Its insistence on the words

Coax, tempt, tantalize, allure, beguile,

Its need to be better than

Every other month,

To shine brighter,

To achieve the pinnacle

In the calendar that Pope Gregory

Arranged for us when Caesar’s failed

To keep track with the actual days.

May: Your first level of meaning is to

Motion, wave, gesture, bid, nod,

Yet I know you are more than that,

Thus the second row of verbs

That more accurately describe

The marker you have placed

In the book of days of my life.

–Shaun Perkins